In our previous blog post about metadata matching, we discussed what it is and why we need it (tl;dr: to discover more relationships within the scholarly record). Here, we will describe some basic matching-related terminology and the components of a matching process. We will also pose some typical product questions to consider when developing or integrating matching solutions.

Basic terminology

Metadata matching is a high-level concept, with many different problems falling into this category. Indeed, no matter how much we like to focus on the similarities between different forms of matching, matching affiliation strings to ROR IDs or matching preprints to journal papers are still different in several important ways. At Crossref and ROR, we call these problems matching tasks.

Simply put, a matching task defines the kind or nature of the matching. Examples of matching tasks are bibliographic reference matching, affiliation matching, grant matching, or preprint matching.

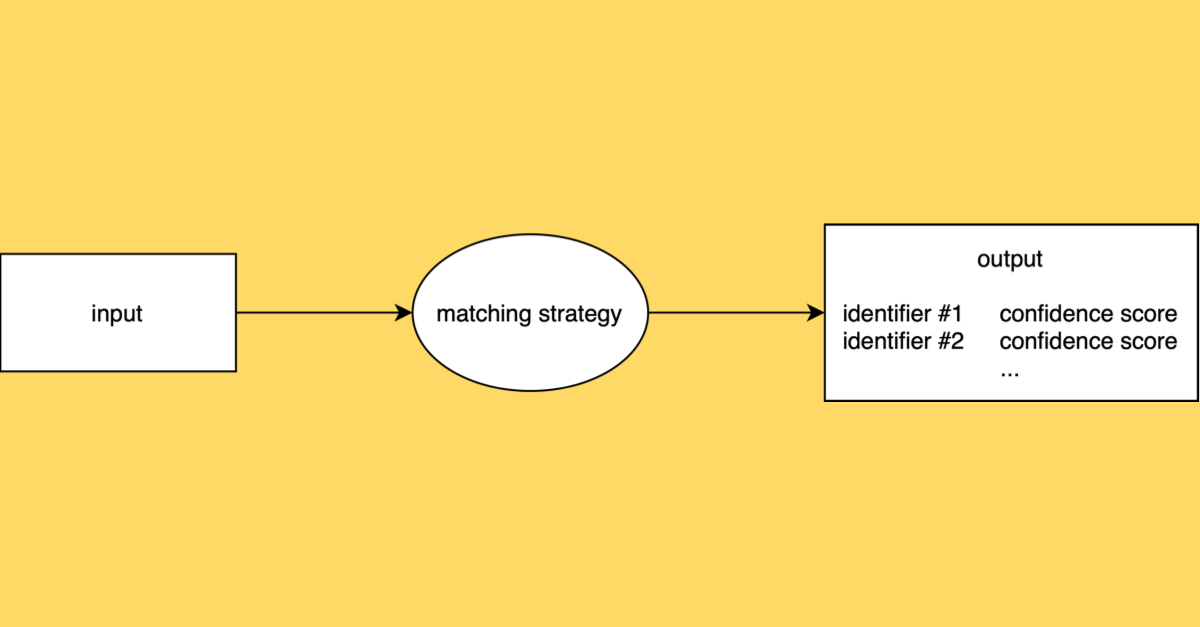

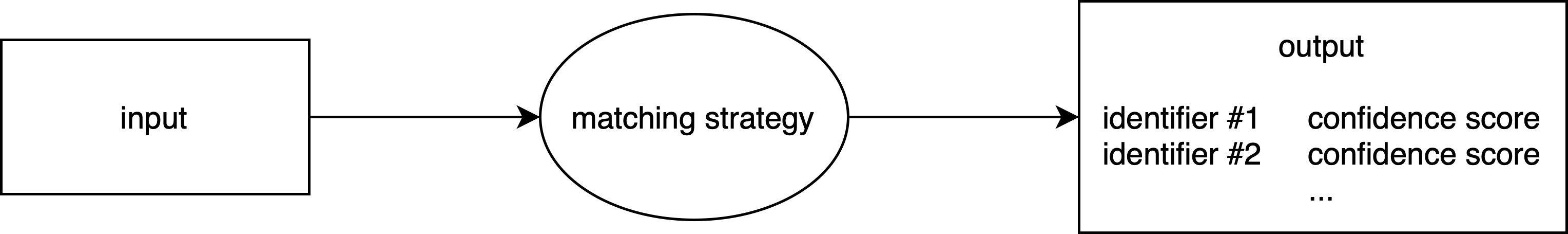

Every matching task has an input, which is all the data that is needed to perform the matching. Input data can come in many shapes and forms, depending on the matching task. For example, all of the following could be inputs to a matching task:

Department of Molecular Medicine, Sapporo Medical University, Sapporo 060-8556, Japan

<fr:program xmlns:fr="http://www.crossref.org/fundref.xsd" name="fundref">

<fr:assertion name="fundgroup">

<fr:assertion name="funder_name">

European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program through Marie Sklodowska Curie

<fr:assertion name="funder_identifier">http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/501100000780</fr:assertion>

</fr:assertion>

<fr:assertion name="award_number">721624</fr:assertion>

</fr:assertion>

</fr:program>

Everitt, W. N., & Kalf, H. (2007). The Bessel differential equation and the Hankel transform. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 208(1), 3–19.

{

"title": "Functional single-cell genomics of human cytomegalovirus infection",

"issued": "2021-10-25",

"author": [

{"given": "Marco Y.", "family": "Hein"},

{"given": "Jonathan S.", "family": "Weissman", "ORCID": "http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2445-670X"}

]

}

Every matching task also has an output. For our purposes, this is almost exclusively zero or more matched identifiers. In the context of a specific matching task, output identifiers may be of a specific type (e.g. we might match to a ROR ID, and never to an ORCID ID). In some cases, there can be a certain target set as well (i.e. matching only to DataCite DOIs). The output identifiers can have different cardinality depending on the task, meaning that the matching task might allow for zero, one, or more identifiers as a result of matching to a single input.

A matching strategy defines how the matching is done. Multiple strategies can exist for a specific matching task. Compound strategies can run other strategies and combine their outcomes into a single result.

In some cases, we may also want the matching strategy to output a confidence score for each matched identifier. A confidence score represents the degree of certainty or likelihood that the matched identifier is correct, typically expressed as a value between 0 and 1. This score may help with post-processing or further interpretation of the results.

To summarise, the anatomy of the matching task can be diagrammed as follows:

How to specify a matching task

Whenever we plan the development or integration of a matching solution, it is good to begin by answering a few basic questions:

What problem do we plan to solve with our matching task? What would we call our matching task and how would we describe it?

What do we expect as the input for this matching task? Which input formats do we need to be able to accept? What information do we expect to find in this input?

What kind of identifiers should be output? Is there a target set of identifiers? Can our matching output zero/one/or multiple identifiers, and under what conditions might that occur?

These sound fairly simple, but the answers to these questions can be remarkably complex. Once one tries to apply these concepts to real-world problems, they might encounter several non-obvious challenges.

For example, one common concern is at what level we should define each matching task. Consider the following problems:

Matching bibliographic reference strings to DOIs.

Example input:

Everitt, W. N., & Kalf, H. (2007). The Bessel differential equation and the Hankel transform. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 208(1), 3–19.

Matching structured bibliographic reference to DOIs.

Example input:

{

volume: "208",

author: "Everitt",

journal-title: "J. Comput. Appl. Math.",

article-title: "The Bessel differential equation and the Hankel transform",

first-page: "3",

year: "2007",

issue: "1"

}

Are those discrete matching tasks (unstructured reference matching vs. structured reference matching), or are they the same task (reference matching) that can accept different types of inputs (unstructured or structured)?

Similarly, let’s compare the following tasks:

Matching affiliation strings to ROR IDs.

Example input:

Department of Molecular Medicine, Sapporo Medical University, Sapporo 060-8556, Japan

Matching funder names to ROR IDs.

Example input:

Alexander von Humboldt Foundation

Are these different matching tasks (affiliation matching vs. funder matching), or the same task with different inputs (organisation matching)?

Defining the boundaries of a matching task can also be difficult. Consider, for example, the need to obtain ROR IDs for organisations mentioned in the acknowledgements section of a full-text academic paper. To begin, one may first extract the acknowledgement section from the full text, then run something like a named entity recognition (NER) tool to isolate the organisation names from the extracted text, and finally match these names to ROR IDs. Is this entire process matching, with the input being the full text of a paper? Or perhaps matching starts with the acknowledgement section as the input? Instead, is it only the last phase, where we try to match the extracted name to the ROR ID, that constitutes the matching task, with the extraction phases being completely separate processes?

There are also important questions related to the expected behaviour of a matching strategy. Consider, for example, developing an affiliation matching strategy where we define our input as “an affiliation string”. What should happen when the strategy gets something else on the input, for example, song lyrics? Perhaps the strategy should simply return no matches, or an error, or we could say that in such a situation the behaviour is undefined and it simply doesn’t matter what is returned. But what should happen if in this input we have the lyrics of Street Life by Roxy Music, a song that mentions the names of a few universities that happen to have ROR IDs?

It is likewise important to consider what should happen if different parts of the input match to different identifiers, like in the following example:

Department of Haematology, Eastern Health and Monash University, Box Hill, Australia

Here, “Eastern Health” matches to https://ror.org/00vyyx863 and “Monash University” to https://ror.org/02bfwt286. Should the matching strategy return all the identifiers, one of them (if so, which one?), or nothing at all?

Similar questions arise when it is possible to match to multiple versions (or duplicates) in the target identifier set. This can happen, for example, in the context of bibliographic reference matching or preprint matching. Multiple matches may occur when there are different editions, reprints, or variations of the same publication in the target dataset, each with its own unique identifier.

If you are waiting for an answer to these questions, we unfortunately must disappoint you here. These can only be answered in the context of a specific problem, considering who the users are and what it is they need and expect.

Did you notice any other subtleties related to metadata matching and its concerns? Are there other non-obvious questions that should be considered when planning to develop or integrate metadata matching strategies? Let us know—we’d love to hear from you!

Feed

Categories

Archives

Tags

- adoption

- annual-meeting

- api

- aps

- caltechdata

- cambridge-university-press

- clarivate

- clear-skies

- coki

- communication

- community

- cris

- cross-post

- crossref

- curation

- curvenote

- data

- datacite

- datasalon

- development

- digicorepro

- digital-science

- discovery

- dryad

- earthscope-consortium

- europepmc

- facilities

- fairsharing

- feedback

- figshare

- funders

- governance

- grei

- grid

- guest-post

- hhmi

- hierarchy

- highwire-press

- implementation

- integrations

- interviews

- inveniordm

- jobs

- latin-america

- machine-learning

- matching

- metadata

- metadata-game-changers

- mps

- mvr

- nwo

- oareport

- oaworks

- open-access

- open-infrastructure

- openalex

- optica

- orcid

- osf

- persistent-identifiers

- pidapalooza

- pids

- posi

- prototype

- publishers

- publishing

- registry

- repositories

- requests

- research-integrity

- researchequals

- resources

- rockefeller-university-press

- rrid

- schema

- scholastica

- silverchair

- skgs

- steering-group

- straininfo

- sustainability

- symplectic-elements

- team

- usdot

- web-of-science

- working-group

- zenodo