In our previous entry in this series, we explained that thorough evaluation is key to understanding a matching strategy’s performance. While evaluation is what allows us to assess the correctness of matching, choosing the best matching strategy is, unfortunately, not as simple as selecting the one that yields the best matches. Instead, these decisions usually depend on weighing multiple factors based on your particular circumstances. This is true not only for metadata matching, but for many technical choices that require navigating trade-offs. In this blog post, the last one in the metadata matching series, we outline a subjective set of criteria we would recommend you consider when making decisions about matching.

Openness

Matching tools come in many different shapes and sizes: web applications, APIs, command-line tools, sometimes even enchanted crystal balls showing matched identifiers emerging from a mysterious mist! No matter what form they take, an important consideration is whether the source code and all the related resources for the matching are openly available.

Picture of the Enchanted Crystal Ball Matching interface to the affiliation endpoint of the ROR API. Source code openly available at https://github.com/adambuttrick/mysterious-crystal-ball-matching.

Matching strategies that are either closed-source, or rely on closed-source services for their matching logic, make it difficult to fully understand and explain matching processes. This lack of transparency also makes it impossible to adjust or improve the matching logic, since we cannot understand or improve code we cannot see.

Users are similarly impeded from identifying flaws or suggesting improvements to processes they are unable to examine. By blocking this community participation, we also lose the proven cycle of real-world testing, refinement, and validation that has strengthened myriad of open source projects. The cumulative impact of both minor and major community-driven refinements over time is incredibly valuable and should not be underestimated.

Using open source matching will also help build trust in the matching workflows and results. This is one reason why open source is one of the tenets of the Principles of Open Scholarly Infrastructure, adopted by Crossref, DataCite, ROR, and other organizations who build and maintain open scholarly infrastructure.

When evaluating matching strategies, we strongly recommend prioritizing those that are fully open source. This not only ensures their transparency and trustworthiness, but also allows for the kind of continuous improvement that results from this visibility and community engagement.

Explainability

In terms of our ability to understand and improve a matching strategy, using an open source model is only the first step. What typically matters most in the context of building and maintaining matching services is that we are able to understand their underlying code and have a clear model of how matches are derived from their corresponding inputs. Even if the matching code itself and all of the resources used in the matching are open, if they are poorly documented, lack reproducibility or tests, or are otherwise opaque, there is no guarantee that it will be possible to understand or improve the strategy. Striving for a high level of interpretability in our matching plays a determinative role in how well we can understand and modify our strategies in the future.

Being able to explain the behaviour of the matching will also help you to respond to and incorporate user feedback. When users encounter errors, you will be able to do things like advise them on how to modify or clean their inputs so that the results are better. Conversely, examining the behaviour of the strategy relative to user inputs and feedback can provide you with ideas for improving the matching.

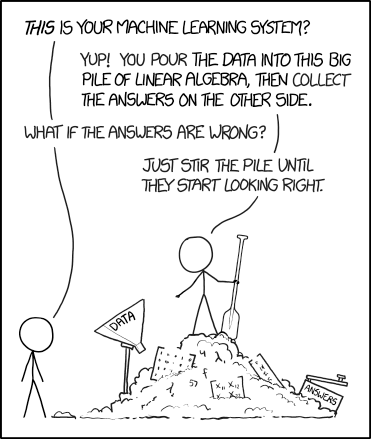

Typically, heuristic-based strategies, such as those that use forms of search or string similarity measures, like edit distance, are easier to explain than, say, machine learning models. If a strategy uses machine learning, at least some internal decisions might be made by passing data through a complex network of algebraic equations. Those can be mysterious, non-deterministic, and are famous for being hard to interpret.

Randall Munroe, Machine Learning, xkcd https://xkcd.com/1838/

This doesn’t mean they should be avoided entirely – we have built and use many machine-learning based tools ourselves! Instead, it is a good idea to weigh how their inherent lack of explainability could affect your ability to continue work on the strategy and respond to user needs, relative to all the available options.

Complexity

Complexity is another aspect that can greatly affect how easy it is to maintain the strategy. Complexity is related to how many different components the strategy has and how difficult they are to use and maintain. When a strategy has multiple interconnected parts, each component becomes a potential failure point that requires discrete assessment and maintenance.

Consider, for example, two different approaches to a matching strategy: one that uses a single machine learning model versus another that uses an ensemble of models. A single model requires maintaining one set of training data, a single training pipeline, and one deployment process. If the model’s performance unexpectedly deteriorates, whether because of an issue with the training data, a configuration error, or the need for additional input sanitization, the source of the problem is easier to isolate and fix.

The ensemble, by contrast, combines multiple, specialized models, each requiring its own training data, tests, updates, and deployments. If one model in the ensemble is found to reduce the performance of the strategy, the interdependence between models can cause this degradation to cascade through the entire system and undermine its overall reliability. Correcting for these errors becomes more challenging. If fixing one model’s performance requires retraining or adjusting its outputs, this could require recalibrating the entire ensemble to maintain the balance between models, identify regressions, and prevent new errors from emerging.

In general, preferring simpler strategies not only reduces operational overhead, but also makes it easier to diagnose issues, test changes, and iterate on user feedback. When problems arise, having fewer moving parts means less places to look for the root cause and fewer components that could be affected by any fixes.

Flexibility

The metadata to which we match grows and changes over time. New records are created, existing ones are updated, with schemas changing and evolving alongside. The resources that underlie our matching are also not static. The libraries we depend on may deprecate features between versions or the taxonomies we used to categorize results might undergo significant revisions. We thus rarely have the luxury of deploying a matching strategy once and using it forever without any changes. A good strategy has to be flexible enough to adapt to such changes, with this adaptation also being both technically feasible and practical to implement.

Much of this flexibility is also determined by a matching strategy’s ability to incorporate new data. Strategies that use continuously updated databases or indices can immediately match against new metadata as it appears in the system. By contrast, some machine learning-based approaches require training on target matches and can thus be limited in flexibility and face more constraints. While some models can be incrementally updated to recognize new matches, others require retraining from scratch to incorporate these changes - a process that can be both time-consuming and resource-intensive.

Paying close attention to a strategy’s flexibility and favoring this aspect, when possible, can significantly impact its long-term viability. When comparing different matching strategies, flexibility should thus be a primary concern in your decision-making process.

Resources

Matching strategies can vary significantly in their resource requirements, including things like CPU and GPU utilization, memory consumption, storage capacity, and network bandwidth. These requirements are directly related to infrastructure costs and energy consumption, so when evaluating a matching strategy, it is necessary to assess its resource demands across all phases of the matching lifecycle. This includes things like initial model training, re-training, index construction, updates and management for all aspects of the strategy, as well as the real-world processing of matching requests. It is a good idea to measure and monitor resource usage carefully in considering which strategies to use, as the best performing strategy may also be too resource intensive to run as a service or might grow to this state over time with additional utilization.

Speed

Matching strategies can operate at a wide range of speeds, from milliseconds to minutes per match. Since the overall response time of a strategy can affect both system scalability and user experience, we should always assess the strategy’s performance for different usage scenarios and scales of data. While some strategies might perform adequately with small datasets, they can also exhibit exponential slowdowns as data volume and complexity increases or as concurrent requests grow in number. We should therefore consider carefully how requirements for matching speed might evolve with increased usage, data complexity, and total anticipated growth. The fastest matching strategy might not always be the best choice if it comes at the cost of reduced accuracy or requires large amounts of resources, but unacceptable latency can make an otherwise excellent strategy unusable in practice for many use cases.

Putting it all together

The typical life cycle of developing a metadata matching strategy is as follows:

- Scoping: we define the matching task, along with its inputs and outputs.

- Research: we research what existing strategies are available for our task and/or we develop our own.

- Evaluation: we evaluate all available strategies, internally or externally-developed, exploring all of the aspects described above.

- Decision: we choose which strategy (if any) we want to use in our production system.

- Production setup: we prepare the production models, indexes, and other resources needed for the matching.

- Maintenance: we monitor and adapt the strategy relative to changing data, user feedback, and new resource requirements.

In practice, these phases do not happen all at once, nor in this strict order. Often we need to proceed through multiple iterations of them to arrive at the best strategy. For example, if initial evaluation of a strategy yields poor results, we might return to the research phase to investigate other strategies or refine our understanding of the task. Often, during the maintenance phase, we receive feedback from users that indicates potential areas of improvement and then pursue them with a new round of research and evaluation.

As we cycle through these phases, ideally all the aspects described in this entry, along with the results of the evaluation, would be taken into account. Of course, this means that these decisions have to be based on multiple criteria and by making trade-offs between their performance and all other considerations. In making these complex and difficult choices, it is useful to consider two primary questions:

- Are any of the considered matching strategies good enough for our use case?

- Out of all the considered strategies that are sufficient for our use case, which would be the best?

The first question requires us to create clear and quantifiable criteria that allow for eliminating some of the potential strategies. As we have indicated, these could include things like the strategy being open source, minimum performance baselines using measures like precision or recall, and operational thresholds, like the strategy being able to return results quickly, relative to user expectations or the volume of data to be processed. It should be fairly easy to test these requirements and eliminate any strategies that fall short of them. If the strategies are difficult to assess, that is likely a mark against them.

If no strategies meet these criteria, we have two options: either to abandon matching entirely or to reassess and relax our criteria to align with the available options. While the former is always an option, adopting a more pragmatic lens, framing in terms of potential value (or harm) to the users, might be beneficial. Sometimes we approach matching tasks with too high expectations and a dose of realism helps us to re-center our perspectives. After more consideration, you might decide that your criteria were too stringent or realize that you need to better define and decompose the tasks to fit the available options.

When multiple strategies appear viable, the selection process becomes more nuanced. When evaluating strategies across these various dimensions, we should try to avoid placing undue weight on minor performance differences. Evaluation metrics are useful estimates of performance, but do not always translate to real-world applications and changing data. In cases where a more complex strategy offers only marginal improvements over a simpler alternative, the maintenance and operational benefits of the simpler solution often outweigh small performance gains.

This concludes our series on metadata matching, where we described the conceptual, product, and technical aspects of matching and its applications. We hope this overview was instructive and helps you to make better decisions about the use of matching in your own tools and services!

Feed

Categories

Archives

Tags

- adoption

- annual-meeting

- api

- aps

- caltechdata

- cambridge-university-press

- clarivate

- clear-skies

- coki

- communication

- community

- cris

- cross-post

- crossref

- curation

- curvenote

- data

- datacite

- datasalon

- development

- digicorepro

- digital-science

- discovery

- dryad

- earthscope-consortium

- europepmc

- facilities

- fairsharing

- feedback

- figshare

- funders

- governance

- grei

- grid

- guest-post

- hhmi

- hierarchy

- highwire-press

- implementation

- integrations

- interviews

- inveniordm

- jobs

- latin-america

- machine-learning

- matching

- metadata

- metadata-game-changers

- mps

- mvr

- nwo

- oareport

- oaworks

- open-access

- open-infrastructure

- openalex

- optica

- orcid

- osf

- persistent-identifiers

- pidapalooza

- pids

- prototype

- publishers

- publishing

- registry

- repositories

- requests

- research-integrity

- researchequals

- resources

- rockefeller-university-press

- rrid

- schema

- scholastica

- silverchair

- skgs

- steering-group

- straininfo

- sustainability

- symplectic-elements

- team

- usdot

- web-of-science

- working-group

- zenodo